Dust collector OEMs constantly try to come in with bids lower than competitors. In an attempt to do so, some baghouse manufacturers offer undersized systems. This article discusses what customers can do to avoid accepting a bid for an inadequately-sized baghouse dust collection system.

By Dominick DalSanto

Dust Collection Expert & Sales Director

Baghouse.com

”I’m sorry, but the other supplier came in lower than you. We went with their proposal over yours.”

I think there are few things I hate hearing more than those words in my position in baghouse sales. I can respect a client who has found a better deal on a comparable system. But I am upset when I hear that my competition came in with a bid lower than mine by recommending a grossly undersized system. As a sales professional, this particularly exasperates me as I feel these OEMs abuse the level of trust placed in them by the customer by offering something they know will not work properly — and because I know how big a problem it is in our industry.

Many sales reps apparently believe in the viability of their plans, and, thus, offer them in good faith, but others have — and will — propose systems that are smaller than customers require knowing that it will not perform adequately. The end result is that vital baghouse systems do not operate adequately, and customers, workers, and the community end up paying the price in the form of higher operating costs, safety hazards, and more pollutants.

The situation can present a major problem for customers as most of them rely on the experience and expertise of baghouse manufacturers or environmental technology experts to recommend a properly sized system. Lacking knowledge on dust collection engineering and industry best practice, customers must rely on others without being able to independently verify their figures.

The question this arises, how can customers prevent this from happening?

Baghouse Case Study at Silver Mine Lab

View of entire testing area including the various hoods and backdraft table connected to a dust collection system.

A few years ago, a silver mining operation contacted us and requested a technical inspection of one of the mine’s baghouse dust collection systems. The task was to examine a small 5,000 cfm system used for venting an onsite testing lab. In the lab, plant personnel conducted daily tests of ore samples taken from various locations in the mine to ascertain which areas had the highest concentrations of silver ore. The process for conducting these tests involved the use of several extremely harmful substances, chiefly lead and cyanide.The main concern was that during some recent evaluations for safety purposes, lead dust had been found on windowsills and in nearby rooms. Additionally, the amount of lead dust found on the clothing of workers in these areas — specifically lab technicians — was found to be several times higher than allowable under MSA standards, leading to one worker requesting a transfer to a different department. In addition, the system itself appeared to function at a very low level of efficiency and “did not seem to run properly,” according to staff.

Problem — An Undersized Baghouse System

Backdraft workstation – Draft (i.e. suction) on the table was so weak it could hardly contain any dust generated on the table

After conducting an inspection and reviewing several elements of the system, I immediately realized it was grossly undersized. It was “designed” to ventilate the testing lab using a series of venting hoods and vented workstations. There were five pickup points in the system that were connected directly to the baghouse, which was located just outside the exterior wall. The first drop point was a large backdraft workstation (Picture #2), 72 in. x 36 in., for mixing the lead and other compounds together with the ore samples. There were three small furnaces — used to heat samples — with venting hoods of 32 in. x 39 in. above them. And there was one tall, ducted workstation, 32 in. x 39 in., used as a back-up for the other mixing station. Venting for everything went straight up through the ceiling to the main trunk (Picture #3), which then ran directly out through the exterior wall and into the baghouse. The main trunk was 12 in. in diameter, tapering to 10 in. then 8 in. then 6 in. The main workstation was connected using a 10 in. duct, and all others used a 5-in. duct (Picture #4) to connect the hoods to the main trunk.

The ductwork above the ceiling of the testing room. The size of the individual branches and the way they connect to each other was not designed according to industry best practice

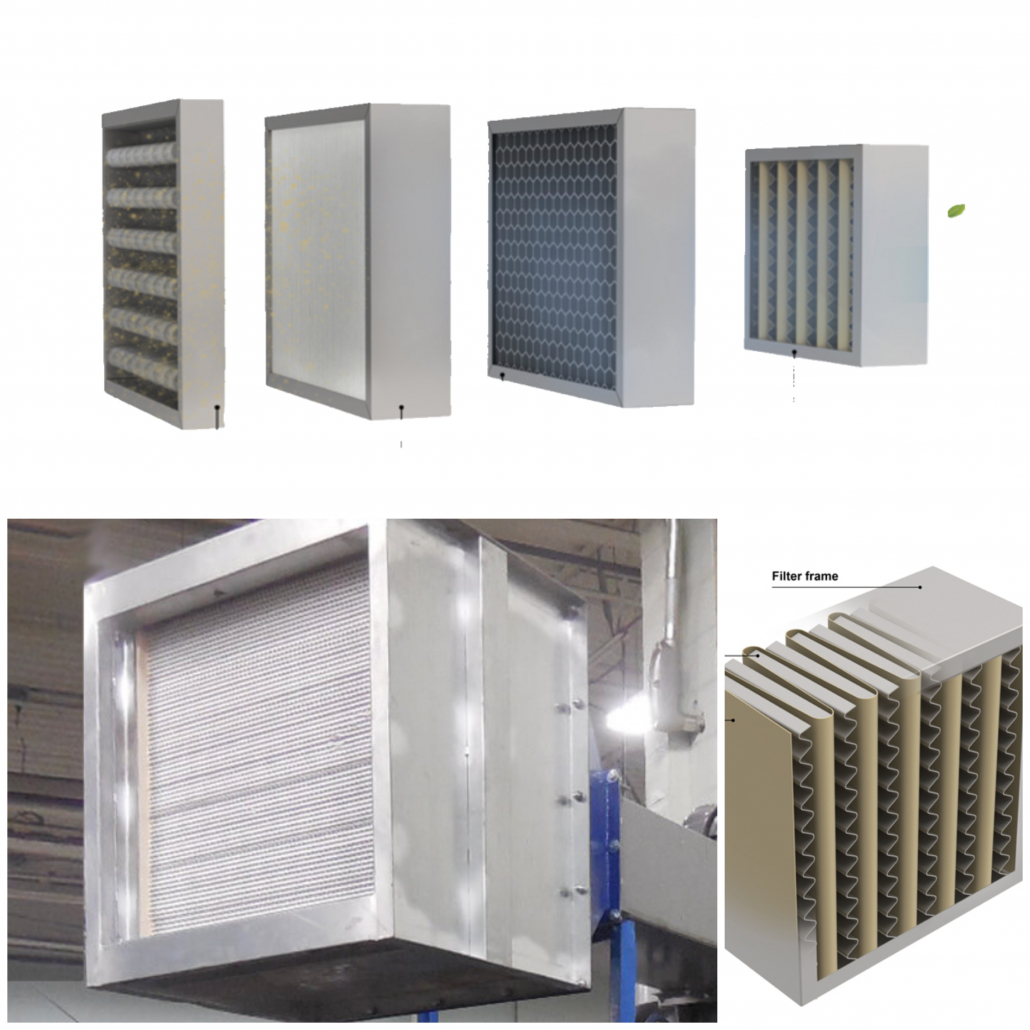

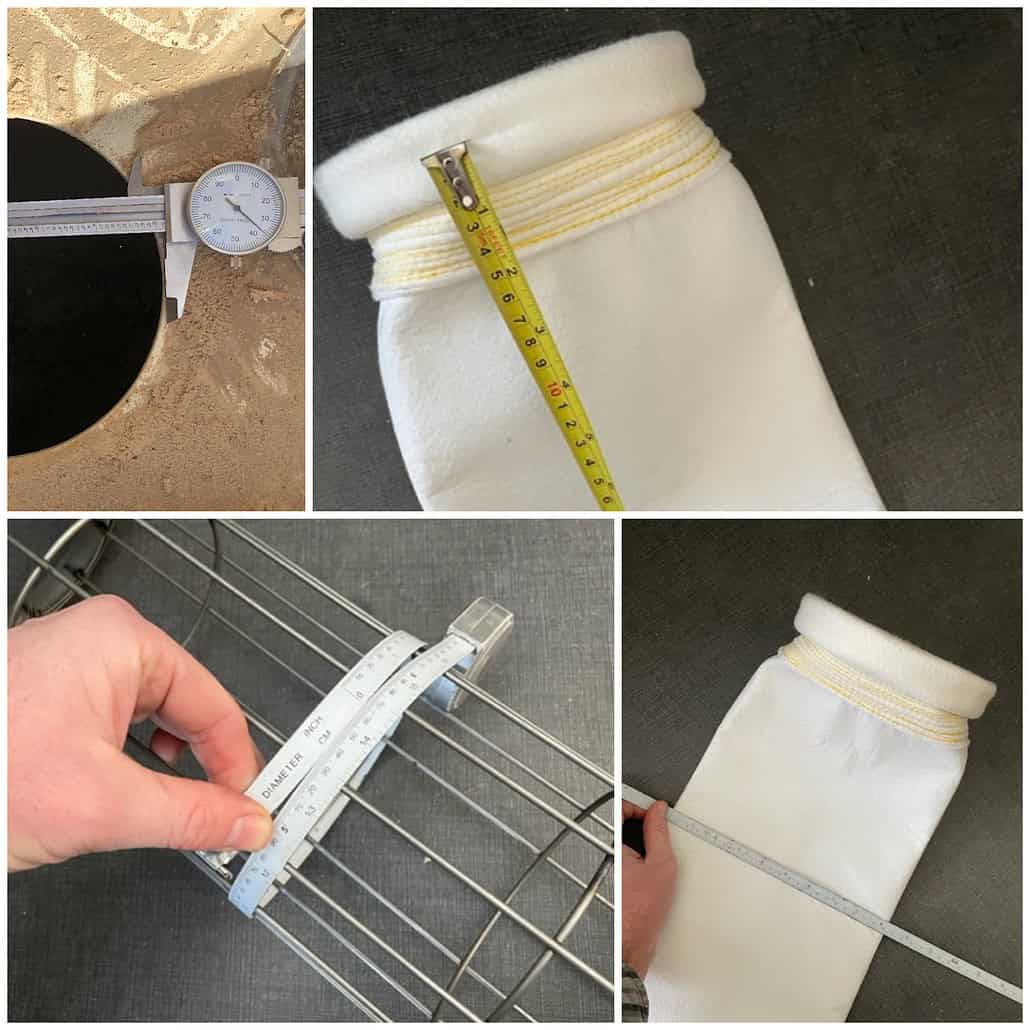

According to the supplier-provided specifications, the baghouse had (49) 5.5 in. x 10 in. bags, and the system fan was rated for 5,043 cfm at approximately 10 in. w.g. of pressure. In this arrangement, the system should have resulted in an air-to-cloth ratio of approximately 7.15:1.

After manually taking airflow readings, I found that the system cfm actually was 3,969. Additionally, when we physically removed a sample bag and measured it, we found it to be 5 in. in diameter, not 5.5 in. as the spec sheet listed. After crunching the numbers, we determined that the air velocity was, at times, below 79 ft./m. This was less than one-50th of the minimum recommend air velocity for this application.

One of the hoods over a test furnace. Notice the lack of curtains and small diameter duct going up out of the hood.

Poor ductwork design, a grossly undersized baghouse, and an equally underpowered fan combined to make this system almost worthless to the facility. (they neglected to size the fan based on the relative elevation and in doing reduced the output of the already undersized fan by another 30%) The effective pull from the system was so weak that one could place a hand directly under the intake on any of the stations and feel almost no noticeable suction — even when the system was running at full power. It was so weak it could hardly lift a piece of paper out of my hand! Obviously, this led to the excessive contamination of the workers and surrounding area.

Why So Small?

The system was designed by in-house personnel, who had no air-handling engineering experience, and a testing lab consulting company. The consultant procured the system from a sales rep organization, which, in turn, procured it from another independent sales rep that worked with the manufacturer. The final cost of the system was more than $75,000 for the baghouse, fan, ductwork, and hoods — much of that being mark-up for all the parties involved. The system was undersized from the start, so while cheaper for the customer, it ended up virtually useless for that customer.

Using even rough calculations, with a minimum conveying velocity of 250 ft./m in the hoods — and that really should have been even higher — the system would have required at least 12,000 cfm to function at an adequate level. Heavy dusts such as lead require high conveying velocities between 4,000 ft/min or more to prevent product drop out. This would mean a much larger system fan, (adjusted to the 4,400-foot geographic elevation of the plant), a baghouse with either triple the amount of bag filters or the use of pleated filter elements to increase filter area, and a completely redesigned ductwork system with a larger trunk and branches, along with better hood design and a damper system to further increase collection efficiency.

Solution — How to Avoid Being Sold an Undersized System

Some may feel that this case study serves only as a horror story to scare potential buyers on the pitfalls of trusting unscrupulous salespeople. I agree that part of the reason for telling this story is to advise you that implicitly trusting any vendor trying to sell you something as large and expensive as a dust collection system is not wise. The main moral of the story, however, is to help you make sure you get the best dust collection system for your needs. In the previously outlined case study, the following steps may have helped prevent this disaster:

1) The first step is to do your homework before you call for quotes. While becoming an expert on every piece of industrial equipment before contacting vendors isn’t feasible, gaining as much knowledge as possible goes a long way to ensuring you get what you need. Knowledge provides you with leverage during the sales process. Since, in this case, company personnel went in completely ignorant of how a dust collection system operates, they were at the mercy of whatever their vendor was going to tell them. This meant they had no idea of air-to-cloth ratios, air conveying velocities, ductwork design, etc.Additionally, where possible, deal directly with a baghouse dust collector manufacture (such as Baghouse.com) as opposed to sales rep organizations, that often have little to no practice experience engineering dust collection solutions.

2) Second, verify vendor calculations. While at times you may be able to determine exactly what size a system you need on your own, you may require assistance. This is especially true with regard to new installations and new processes. There is nothing wrong with asking vendors to assist you, but make sure to review their numbers afterward. This may require a bit of research or even hiring an outside consultant to verify the engineering. In the case study, had plant personnel taken the time to review system specifications proposed by the vendor, people would have found that the figures were far off from accepted industry standards. (See the American Council of Governmental Industrial Hygienists (ACGIH) Manual for standards on minimum air-conveying speeds and system design standards.) This would have exposed that the system was grossly undersized and allowed staff either to correct the problem or to seek a different vendor.

3) Third, seek alternative proposals. Had the company solicited alternative bids, personnel likely would have noticed the obvious discrepancies between them. Additional proposals likely would have shown a large difference in price, owing to the vendor’s undersizing of the system. Other vendors (likely) would have submitted more realistic proposals. Instead of believing that any one supplier somehow may have managed to undercut the competition by such a large margin — while offering an adequate product — the wise course would be to investigate why one bid would come in so much lower than the others and correct any mistakes that may have been made.

Conclusion

Yes, this story is meant to raise concerns over the buying process, but that is a good thing for potential buyers. If they keep in mind the points outlined here, they can avoid the pitfalls of an installing an undersized dust collection system and avoid the complications that can come with it.